13 Mar Divine pronouns? Let God decide

The Church of England has been asked to respond to requests from clergy to use gender-neutral pronouns for God. The question has been referred to the Church of England’s Liturgical Commission. This would be a major variation from the Book of Common Prayer, a foundational text for Anglicanism.

In fact, Anglican churches have been moving towards using more inclusive language for decades. A Prayer Book for Australia, published in 1995, replaced ‘he became man’ in the Nicene Creed with ‘he became truly human’; and in the Gloria in Excelsis in the same publication, the phrase ‘peace to His people’ was replaced by ‘peace to God’s people’. The Australian Hymn Book, first published in 1977 and used by many denominations, has systematically removed the use of male pronouns for generic reference to people. For example, John Bunyan’s muscular lyric ‘He who would valiant be’ was rewritten as ‘Who would true valour see’. These changes did not extend to removing references to God as Father or Jesus as the Son of God.

The recent requests coming from the United Kingdom are more radical. Some clergy are asking for leave to change references to God in their church services to ‘she’ or ‘they’, or perhaps ‘Mother’ alongside ‘Father’, or just ‘Parent’. This is implied in the Reverend Joanna Stobart’s request to the Commission to allow referring to God in a ‘non-gendered way’.

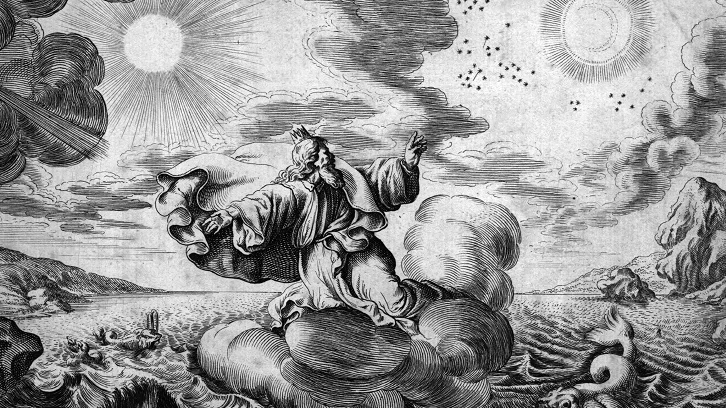

Since the earliest times, Christian theologians and Jewish scholars alike have considered the God of the Bible to be sexless: neither male nor female. This contrasts with Greek and Roman deities who had active sex lives, mating with humans and each other, and having offspring.

In some languages, such as Persian and Indonesian, the need to choose a gendered pronoun doesn’t arise because pronouns do not distinguish male from female. In contrast, the languages in which the Bible is written – Hebrew, Greek, and Aramaic – compel their speakers to use gendered pronouns, and God is referred to as ‘he’ rather than ‘she’. Nevertheless, this usage is not considered to be evidence that God is actually male.

There are a number of passages in the Bible where God is attributed with female characteristics. For example, ‘wisdom’, an attribute of God, is famously personified as female in the book of Proverbs; and in Matthew’s Gospel, Jesus compares himself to a mother hen when he speaks of his love for Jerusalem.

Nevertheless, female metaphors for God do not have equal billing with male metaphors. God is never referred to as a ‘queen’, only as a ‘king’. Furthermore, the worship of gods and goddesses, whose idols possess clearly visible sexual characteristics, is anathema to Biblical religion.

One of the guiding principles of Anglican worship is that the words used should align with Biblical language. This was part of the genius of Archbishop Cranmer, who crafted much of what became the Book of Common Prayer. A challenge for those seeking to de-gender language used for God is that this would be a break with Biblical language. Jesus himself referred to God as ‘Father’ 170 times in the Gospels and never used any other term for God in his prayers. Do Christians of today know better than Jesus how to talk about God?

It is a principle respected by many today that a person has the right to choose the pronouns others use for them. This raises the question of whether it is up to believers to choose God’s pronouns: shouldn’t God be making that choice for ‘godself’? Does de-gendering or re-gendering God send a signal that God lacks agency, and is not a ‘someone’ at all, but just a ‘something’? Isn’t this misgendering God?

This presents Christians with a choice: respect God’s agency by using the language for God that God himself uses in the Bible, referring to God as ‘Father’ and ‘he’; or signal God’s depersonalised impotence by repackaging language for God to suit contemporary gender ideology. Christians who believe in a personal God should allow him to speak for himself about what names and pronouns he wants to be used in reference to him.

This is not just a matter of blind obedience to an archaic text. Although many find the concept of the fatherhood of God deeply problematic because they think it implies patriarchy, control, and dominance, this is not how Jesus speaks of the fatherhood of God in the Gospels. The metaphor of God as Father, and even Abba (‘daddy’), is intended to tell us that God is creator (for we exist because God wants us to); that God is good; and that God wants to do good for all people.

The idea of a personal, loving, benevolent God, who made us and cares for us as our good Father, should not be seen as a poisoned chalice or something to be erased. On the contrary, it reflects a deep hope that human beings, said in Genesis to be made both male and female in the image of God, can aspire to share in God’s inherent goodness. This is presented in the Bible as a point of unity for all humankind. It is a redemptive vision, not a cursed one. It is Jesus’ personal vision of God.

Mark Durie is the founding director of the Institute for Spiritual Awareness, a Fellow at the Middle East Forum, and a Senior Research Fellow of the Arthur Jeffery Centre for the Study of Islam at the Melbourne School of Theology.

No Comments