09 May Sydney Sermons, Islamic Incitement

Since the October 7 atrocity, there has been a string of anti-Jewish sermons delivered in Sydney mosques by Muslim preachers. These have attracted much critical attention in the Australian media.

New South Wales Police, after conducting their own investigations, declared that they have no grounds to take legal action against the preachers. The Jewish community was shocked and distressed by this, and has been exploring the possibility of taking legal action of its own.

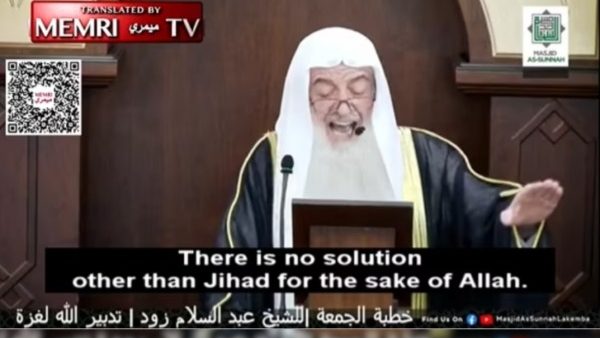

Of the many anti-Jewish sermons, a particularly significant one was delivered at Friday prayers on 9 February 2024 by Imam Abdul Salam Zoud. Extracts of this sermon have been translated by MEMRI.

This sermon is significant for two reasons in addition to its antisemitism. First, Imam Abdul Salam cannot be dismissed as a marginal figure on the extreme fringes of Islam. His expertise in Islam has been recognised by his peers. He is a member of the Australian National Imams Council (ANIC), which admits only Sunni Muslims who have recognised formal qualifications in Islam, and he has been appointed to ANIC’s Fatwa Council, which provides legal rulings (fatwas) to Australian Muslims. Imam Abdul Salam’s membership of this group shows that he is recognised by his peers to have superior expertise in Islamic law. His voice speaks from the heart of Sunni Islam, not from its periphery.

The second reason this sermon is significant is that Imam Abdul Salam incited violent jihad against followers of all non-Muslim religions, including Christians. The relevance of this teaching has been underscored by the 15 April knife attack in Sydney, allegedly by a Muslim youth, on the Assyrian bishop Mar Mari Emmanuel, as a result of which the bishop has lost the use of his right eye. In a video taken in the church immediately after the attack, the alleged attacker is being restrained and is asked by a priest “Who sent you here?” The youth answers in Arabic, “If he had not cursed my prophet I wouldn’t have come here.”

Imam Abdul Salam’s sermon made several points. First, it said that Jews are evil killers, bloodthirsty, treacherous and barbaric. Second, Islam’s destiny is to rule over all other religions, including Jews, but also Christians, Hindus, Buddhists, Sikhs and atheists. Third, the only way – the God-given way – to fulfil this destiny is through jihad. Fourth, Muslims must prepare as much power for this jihad as they can.

By ‘jihad’, Imam Abdul Salam did not mean inner spiritual struggle, but the jihad of conquest, which he said must continue until the end of the world. This is clear on two grounds. First, he referred to the great Islamic caliphates of the past: “none of them conquered the world by peaceful means, negotiations, concessions, or understandings. They conquered it through jihad for the sake of Allah.” He also pointed out that Islamic conquest is not an end in itself. The purpose of the conquest of non-Muslim nations is, from Islam’s perspective, an inherently righteous cause: to remove “obstacles” to the “spreading and rule of Islam”.

Second, Imam Abdul Salam equated jihad with violent fighting when he said, “This is the purpose of fighting (al-qital, an Arabic word which implies killing) and waging jihad against the enemies of Islam …”

Imam Abdul Salam applied this to Palestine, which “will only be restored through jihad”. However, he also made clear that jihad conquest is “the only solution when it comes to the infidels” in general, including “the Jews, the Christians … the Buddhist, Sikh and Hindu polytheists, as well as the atheists – all of them are against you, O Muslims”.

The points made in this sermon are derived from the Qur’an or the Sunna (the teaching and way of life of Muhammad). For example, the Imam’s claim that Islam must “reign supreme over all other religions” is a paraphrase of Sura 61:9 which says exactly that. When Imam Abdul Salam called Jews “treacherous”, he was echoing the Qur’an’s descriptions of Jews as pact-breakers (Sura 2:27, 4:155 and 5:13). To call Muslims to prepare for jihad, Imam Abdul Salam recited Sura 8:60: “prepare against them whatever you are able of power and steeds of war by which you may terrify the enemy of Allah”.

Such political views are not new to Australia. Imam Abdul Salam was formerly a long-time leader within the Salafist Ahlus Sunnah wal Jama‘ah (ASWJ) movement. In the year after the 9/11 atrocity, the website of the Islamic Information and Support Centre of Australia (IISCA), an affiliate of ASWJ, posted a series of articles that expressed views similar to those recently expressed by of Imam Abdul Salam, including:

- Islam is incompatible with democracy

- anyone who rejects the message of Islam must be fought against

- all Muslims must work to establish the dominance and supremacy of Islam

- all non-Muslim religion is by definition tyranny

- jihad means “to struggle against the disbelievers”

- fighting unbelievers is the highest, most meritorious act in Islam

- if the spread of Islam is inhibited, then the governing authorities must be overthrown.

The antisemitism is also not new. In October 2002, I came across a glossy anti-Jewish brochure which was being handed out to customers by a Lebanese cake shop on Sydney Road, Brunswick. The brochure had been produced by the Islamic Information and Services Network of Australia (IISNA), an offshoot of IISCA. At the time I visited IISNA’s website and found that it contained further antisemitic statements.

It is important to be absolutely clear that all this is not about racism. From an Islamic perspective, Jews are not a racial category but a religious one, a subcategory of kuffar ‘infidels’. The category “Jew” exists in Islamic sources alongside “Christian”, which is also a religious category. This perspective was reflected in Imam Abdul Salam’s sermon, which grouped Jews together with Christians, Hindus, Sikhs and Buddhists. Islamic antisemitism is not racial hatred, but religious.

What to do about all this?

Since 11 November 2023New South Wales has had brand-new anti-vilification provisions included in its Anti-Discrimination Act. This Act prohibits incitement of hatred, serious contempt or severe ridicule of a person or a group on the basis of their religious belief or affiliation.

In August 2023, the Australian National Imams Council welcomed this new law, because it “sends a clear message that religious vilification is not acceptable”. The amendment, they said, is “long overdue, particularly in a climate of increasing Islamophobia and anti-religious sentiment …” ANIC stated that it “is proud to see the amendment made. It [ANIC] has worked tirelessly behind the scenes to advocate for such a change, including providing input as to the approach and provision to be adopted.”

But is this Act fit for purpose? It imposes civil, not criminal, provisions, which means that the police cannot use it to act against antisemitic preachers: someone from the Jewish community would have to make a complaint for the law to be applied. When a preacher has called for Muslims to “terrify the enemy”, and stated that “obstacles” to the spread of Islam are a trigger for jihad, it is understandable that individuals or groups might feel vulnerable and be reluctant to initiate a complaint. Complainants would not merely be taking on an individual; they would be challenging the religious convictions of many in the Islamic community. It also seems unreasonable that the state would leave dealing with this kind of incitement to affected individuals or community organisations.

Another obstacle when applying these new NSW anti-incitement provisions is that an exemption is provided for any act “done reasonably and in good faith” for “religious discussion or instruction purposes”. Imam Abdul Salam could argue that he was merely providing religious instruction in accordance with the precepts of Islam. Countering this might be difficult. He could insist that his message accurately reflects the teachings of the Qur’an and the Sunna. In his defence, one can hardly expect a secular tribunal to rule that his views are Islamically invalid. After all, Imam Abdul Salam is recognized as being qualified to tell other Muslims what Islam is or is not.

It would also be difficult to determine what “reasonably” and “in good faith” should mean in this context. Based on inconsistent rulings in previous vilification cases, there is uncertainty about how tribunals and courts are to interpret these expressions.

One could argue that civil anti-vilification provisions are of little value, only serving to increase tensions between groups in the community. What is needed are criminal provisions targeting incitement to violence. As it happens, there is another legal option in NSW that may be applicable. Under section 93Z of the NSW Crimes Act 1900, a criminal offence is committed by someone who “intentionally or recklessly … incites violence towards another person or a group of persons” on the grounds of someone’s religious belief or affiliation. In this case, no defence is available for religious teachings, but prosecution under section 93Z can only be commenced by the police or the Director of Public Prosecutions. So far, the NSW authorities seem to have taken no action; however, the NSW Attorney General has announced a review of section 93Z.

Section 93Z defines holding or not holding a religious belief as a religious belief. Surely when a respected religious leader teaches that violent jihad “for the sake of Allah” is Allah’s will and “the only solution when it comes to infidels” (i.e. non-Muslims), including Jews, this is incitement to violence on the grounds of someone not being a Muslim. Do the police and the DPP not have sufficient Islamic religious literacy to be able to join the dots?

A deeper difficulty that may face bureaucrats considering launching a complaint against Imam Abdul Salam using either the Anti-Discrimination Act or the Crimes Act is that the pursuit of the complaint would focus public attention on Islamic teachings that are inimical to interfaith harmony and peaceful co-existence. It could expose as questionable or even fanciful the claim that jihad is a personal interior struggle. Imam Abdul Salam’s defence could also challenge the assumption that “Islamophobia” is an irrational hatred. A public legal process would come up against multiculturalism’s insistence that certain minority groups require special acknowledgement and affirmation.

In all this, the Australian Human Rights Commission is missing in action. It is surely a crisis of cognitive dissonance that has caused it to avoid calling out the Sydney anti-Jewish sermons as religious bigotry. Instead, it has announced “further anti-racism work” in response to what it calls “an increase in racism targeting Palestinian, Muslim, Arab, and Jewish communities”. This is misdirection and obfuscation which will do nothing to solve the very real problem of religious incitement.

At the same time, Australian security authorities might also be concerned that since the main trigger for jihad is the existence of “obstacles” to the spread of Islam – according to the Imam’s sermon as well as other statements by Muslim authorities – a criminal conviction would be considered an “obstacle” to the spread of Islam in Australia, which could therefore incite a violent response. A conviction for inciting violence could incite more violence.

There is a long-term systemic problem in Australia’s approach to containing the flow of radical Islamic indoctrination. Back in 2002, the Ahlus Sunna wal Jama‘ah website posted an article that discussed a famous fourteenth century fatwa issued against Genghis Khan by the renowned medieval Muslim scholar Ibn Kathir. This fatwa declared that Genghis Khan should be fought against (and killed) by Muslims because he did not rule by Islamic law. The article went on to state that this fatwa is still open against anyone who does not rule by Islamic law. An obvious implication is that the life of any politician is forfeit if they do not rule by Islamic law.

More than a decade after encountering this fatwa, I asked an ASIO official whether posting Ibn Kathir’s fatwa on a website was actionable. He said no: the authorities take action when they become aware of an actual plan to do an illegal act.

Surely that is far too late, and far too high a bar.

Since October 7, the British government is having to provide heightened protection for MPs due to the increased number of death threats they have been receiving. MP Mike Freer has announced he is standing down at the next election. He cited “a constant string of incidents”, including death threats, abuse, and narrow escapes, and reported that he only narrowly missed being attacked by MP David Amess’s killer, Ali Harbi Ali, by “a stroke of luck”. He said that while additional protection was welcome, the greater issue is why people have felt “emboldened” to attack MPs: “Unless you get to the root cause, then you’re just going to have a ring of steel around MPs. And our whole style of democracy changes.”

It must be acknowledged that Islamic radicalism is by no means the only source of threats to British MPs. Several British MPs were killed by members of the IRA, and in 2016, Labour MP Jo Cox was killed by a right-wing extremist, Bernard Kenny, who shouted “Britain first!” as he attacked her.

Nevertheless, one potential root cause of someone feeling emboldened to do violence to a politician – a Jew, a Christian, or anyone else who might be considered an “infidel” – is that they have been taught that “jihad for the sake of Allah” is the “only solution when it comes to the infidels”.

Meanwhile, Australian “infidels” (non-Muslims) seem strangely unwilling to do anything about a pattern of religious incitement targeting them which has been around for decades.

Why are our heads so firmly planted in the sand? Are we really willing to stand by and let “our whole style of democracy”, our very way of life, be profoundly changed by religious incitement? If we are not, then something needs to change – something that goes to the very root of how we understand Islam and the role it plays in our society.

Mark Durie is the founding director of the Institute for Spiritual Awareness, a Writing Fellow at the Middle East Forum, and a Senior Research Fellow of the Arthur Jeffery Centre for the Study of Islam at the Melbourne School of Theology.

Carole Armstrong

Posted at 18:20h, 09 MayVery helpful article. What a complex and challenging time we face. I hope this is shared far and wide.