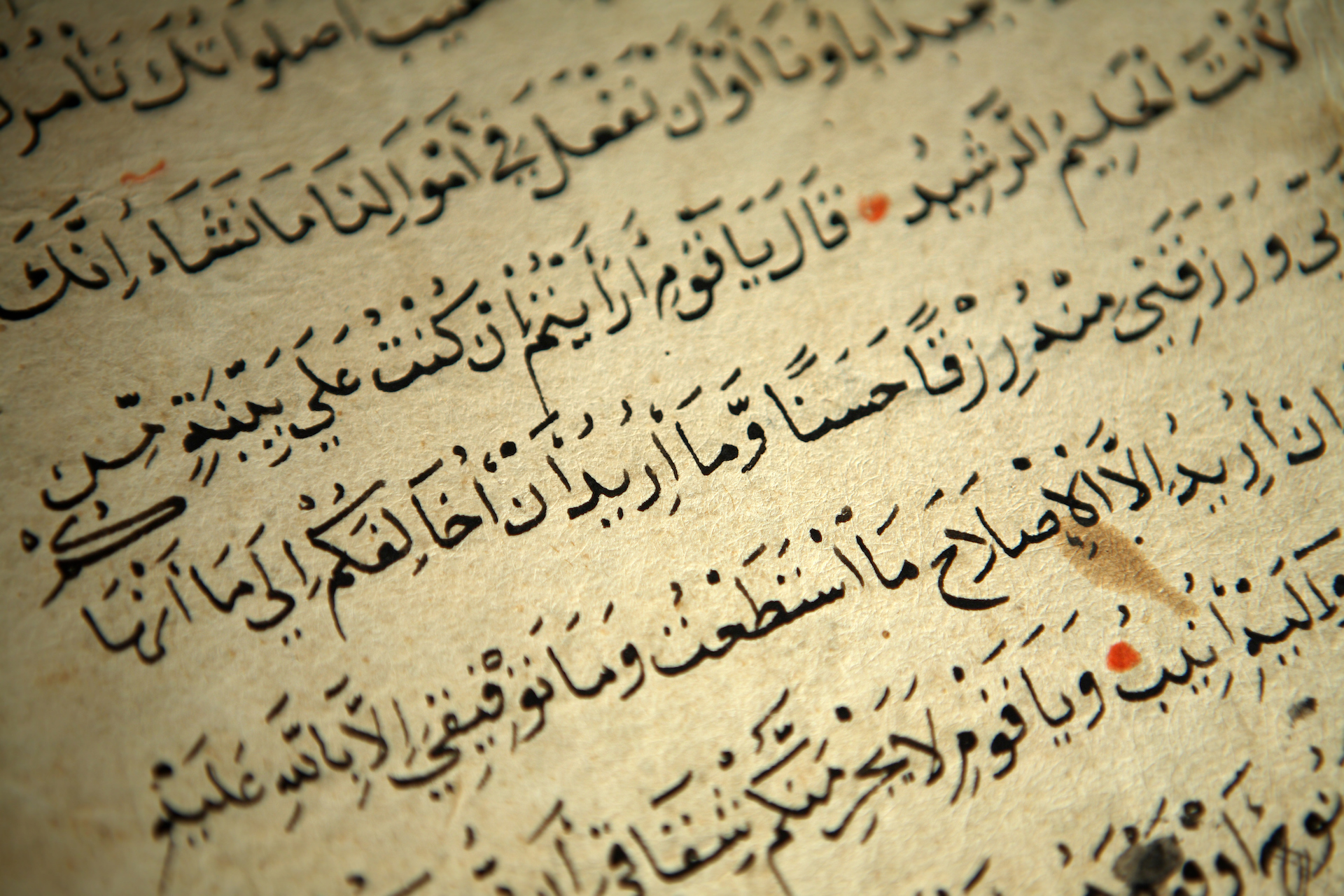

07 Jun The Qur’an’s Turn to Violence

The Problem of Peace vs. Violence

It is widely recognized that, on the topic of violence, the Qur’an speaks with more than one voice. Some verses speak for peace, and others for war. The conventional explanation is that the difference hinges on the migration of the early Muslim community from Mecca to Medina: in Mecca Muslims were persecuted while Muhammad and the Qur’an preached non-violence and tolerance, but in Medina an Islamic state was established, and Muhammad gathered an army, leading it to triumph in battle against non-believers.

A Conventional Explanation

A conventional Islamic theological interpretation is that in Mecca Muhammad and his community were weak, vulnerable and persecuted, so Allah wisely commended patience and forbearance. However when their power was established in Medina the Muslims were commanded to fight for the cause of Allah, ushering in the triumphant advance of the religion.

It is indisputable that there is a progression from peace to violence in the Qur’an. But is the conventional explanation for that shift supported by the text of the Qur’an itself? Does this explanation make the best sense of the Qur’an?

A Different Story to be Told

In my recently published book, The Qur’an and its Biblical Reflexes, I argue that the traditional explanation is based on a misreading. Setting aside the whole Mecca-Medina narrative (for a whole host of reasons), I argue that if we read the Qur’an with an ear for changes in its theology around the transition between the (so-called) ‘Meccan’ and ‘Medinan’ verses, a different story emerges. This is a story about a crisis of faith and how it was successfully resolved.

To understand what was happening when the message of the Qur’an changed, we need to focus on the message itself. The earlier chapters of the Qur’an warn hearers that if they do not repent, they will be punished in this life and the next. Not only does the fire of hell await them, but in this life a ‘nearer punishment’ will come down on their heads in the form of a destructive act of God. Many stories are reported in the earlier passages of the Qur’an which tell how Allah destroyed past generations of people who ignored warnings brought by messengers, by violent interventions such as flood, earthquake, windstorm or fire from heaven.

Alongside these dire warnings, the Qur’an also promises success in this life and the next to those who repent and believe.

How did people receive this doomsday preaching? Not all that well. The disbelievers began to mock the Qur’anic ‘Messenger’ (named in the Qur’an as Muhammad, or ‘praised one’), asking when this great disaster was going to come. ‘Bring us what you promised’ (Sura 7:70), they would say, complaining that it was all taking far too long. The Qur’an wryly comments that ‘they seek to hurry the evil’ (Sura 13:6), but what they were really saying was that the Messenger had made it all up. The disbelievers also mocked the Messenger in many other ways, which is reported in surprising detail in the Qur’an (e.g. Sura 37:36).

A Crisis of Faith

How were the believers taking this? The Qur’an reports that the Messenger and his band of followers were getting anxious. Responding to this anxiety, the Qur’an counsels patience and emphasizes that the Messenger is only a warner, so he is responsible for nothing but the clear delivery of the message (Sura 29:18). The timing belongs to Allah.

For a while things are not looking good for the Qur’anic believers. In addition to the mockery, they are being ill-treated, and some are even being expelled from their homes. There are references to the Messenger suffering distress and doubt (e.g. Sura 10: 46, 65; 11:17), although he is comforted with the thought that past messengers had also suffered from feelings of hopelessness (Sura 12:110). Some believers are tempted to turn away (Sura 21:109, 16:82) and some are giving in to that temptation (Sura 13:25). The success they had all been promised seems as elusive as the punishment of disbelievers is delayed.

This was fundamentally a crisis of faith, a theological crisis. In The Qur’an and its Biblical Reflexes I call it an Eschatological Crisis. The very existence of the movement of believers was coming under threat. Waiting for God’s ‘nearer punishment’ could only go on for so long. When everything keeps continuing on as normal, a doomsday prophet’s authority begins to ebb away.

The Theological Transition: The Crisis Is Resolved through Violence

The crisis is resolved in a way which the preceding revelations has not anticipated. It is announced to the believers that the promised and long-awaited act of punishment had arrived in the form of violence by human hands: ‘fight them, and Allah will punish them by your hands’ (Sura 9:14). It is not to be by earthquake or fire from heaven, but by the swords of the believers that God’s hand would bring the nearer punishment. Referring to a battle, as if to reassure believers, Allah tells them that it was not they, but Allah who killed, and they did not throw spears, but Allah threw them (Sura 8:17). To describe this violence, the Qur’an also uses language which previously had characterized acts of God and the fire of Hell: it is called a ‘painful punishment’ and a ‘tasting’ (i.e. of what will come to them in the Fire). The pattern of Allah punishing past generations by earthquake, flood, storm or fire had previously been described as the unchanging ‘path of Allāh’; after the crisis, the believer’s fighting comes to be described as striving (jihād) in ‘the path of Allah’.

I term the shift in thought which resolves the crisis, the Theological Transition, so the division in the Qur’an is not between Meccan and Medinan suras, but between pre- and post-transitional suras.

By embracing violence the Messenger and his followers move on from passively waiting for a future divine punishment, to become active agents of divine retribution in the present. In essence, the switch from peace to war is not about defensive fighting, nor even a reaction to persecution. It is a validation of the Messenger’s doomsday message, which saves the Qur’anic movement and its Messenger from sectarian oblivion.

This explanation for the turn to violence makes a whole lot better sense of the actual text of the Qur’an than the conventional account. In The Qur’an and its Biblical Reflexes I document in great detail the many theological and rhetorical adjustments which the Qur’an’s makes to support and validate this shift. For example, after the turn to violence we find that the Qur’an no longer reports that disbelievers are calling for divine punishment to be ‘hurried’ (since it had already arrived).

Consequences of the Transition

One of the most striking adjustments after the Theological Transition is a change in the understanding of the role of messengers. Before the Transition, it had been repeatedly emphasized that past messengers were just ‘warners’, whose only task was to deliver the message. However after the Transition, messengers become the leaders of the fighting faithful (‘how many a prophet has fought, and with him many thousands’ Sura 3:146), and stories of past messengers are being refashioned to reflect this new reality. A change also takes place in the position and status of the Qur’anic Messenger, as he is now one who must be obeyed rather than just one whose message is to be believed. It is retrospectively asserted that this was always true of all previous messengers (‘we have only sent messengers to be obeyed’ Q4:64). In this way the messenger acquires what E. A. Rezvan has called ‘all-embracing personal power’. We can also note that these changes are problematic for the internal consistency of the Qur’an’s theology. Although before the Transition the Qur’an had repeatedly asserted that there can never be a change in the ‘path of Allah’ (Sura 33:62; 35:43; 48:23), after the Transition there was a highly significant, indeed world-altering, change.

Why Didn’t Anyone See This Before?

The Qur’an is not an easy book to read for understanding. Its suras (chapters) are not in any logical or chronological order, and within individual suras a wide variety of themes and ideas can be covered, in a flowing stream of thoughts which are not organized into an obvious rhetorical structure. It can be very easy to miss things. This also means that readers tend to be very dependent, when reading the Qur’an for understanding, on the standard narrative frame provided by the life of Muhammad. People see what their eye is directed to, and the conventional biographical frame tends to direct readers’ attention away from the inner theological development of the text, including the Eschatological Crisis. The biography of Muhammad directs us to read the Qur’an in the light of the fledgling Muslim community’s struggle for power in the face of rejection and hostility. In this way, the conventional biographical frame pushes the theological frame of the Qur’an to one side, obscuring it from view.

I came to the understanding outlined here as the result of a deliberate decision to make sense of the Qur’an in its own terms, without ANY reliance upon the biography of Muhammad (with which I was nevertheless very familiar). After coming to the conclusions reported here, I did however find my analysis confirmed in an excellent book by David Marshall, God, Muhammad, and the Unbelievers. Key aspects of what I was seeing Marshall had already discerned, and I give him a lot of credit in my book.

Conclusion

In summary, the ‘inner’ theological history told by the Qur’an itself is not that of a persecuted community which found triumph through migration and state-formation, from where it took up arms against its persecutors. That may be the story told by biographical materials about Muhammad gathered together centuries after the Qur’an was written, but it is not the story the Qur’an tells. Although there is persecution and triumph in the Qur’an, a more careful reading of the Qur’an’s text reveals a movement which was faltering under the weight of the non-arrival of a prophesied doomsday scenario. This movement was then saved – and transformed – by a shocking and epoch-making announcement that the swords of believers were to be considered an act of God. The rest, as they say, is history.

This was first published by the Interface Institute.

Dr. Mark Durie is an academic, human rights activist, Anglican pastor, a Shillman-Ginsburg Writing Fellow at the Middle East Forum, and Adjunct Research Fellow of the Arthur Jeffery Centre for the Study of Islam at Melbourne School of Theology.

No Comments