09 Apr Were the ‘Dark Ages’ Really Dark?

Today just about anything and everything may be objected to as ‘sending us back to the Dark Ages’, including restrictions on subsidies for renewal energies, growth in faith schools, acts of terrorism, destruction of art works, the popularity of right-wing parties in Europe, the rise of superbugs, and denial of global warming. The Dark Ages have become proverbial.

According to popular myth, modern Europe emerged through the Renaissance and Enlightenment from the ‘Dark Ages’, a period of cultural stagnation and superstitious obscurantism, poor hygiene and worse dentistry which set in after the decline and fall of Imperial Rome. The popular narrative tells us that Europe was rescued from its illiberal, ignorant past by reason and science, which ushered in modern progress, emancipating humanity from the stranglehold of religious oppression.

The idea of a dark period following on from Roman and Greek Antiquity was an invention of the Renaissance, and further promoted during the Reformation and the Enlightenment. It was first put forward by Petrarch, the founder of Humanism, in the 1330’s, who believed that Italy was on the verge of entering a new and better age, of which his own contribution was an example. Later, Protestant reformers adopted as their motto post tenebras lux ‘after darkness light’, intended as a pejorative reference to the previous influence of Roman Catholicism. At the start of the 17th century, the Italian historian Caesar Baronius was the first to use the term ‘dark ages’ to refer to the period between the end of the Carolingian Empire in 888 and the Gregorian Reforms of 1046. He called this period ‘dark’ for a technical reason, because it left behind so few written texts. However in the Enlightenment, writers such as Kant and Voltaire used the phrase ‘dark ages’ to accuse the Middle Ages of backwardness.

Today the term ‘dark ages’ is rarely used by professional historians, because it reflects a simplistic, pejorative and misleading understanding of the history of Europe. The reality is that the thousand years between the decline of the Roman Empire and the Enlightenment were anything but ‘dark’.

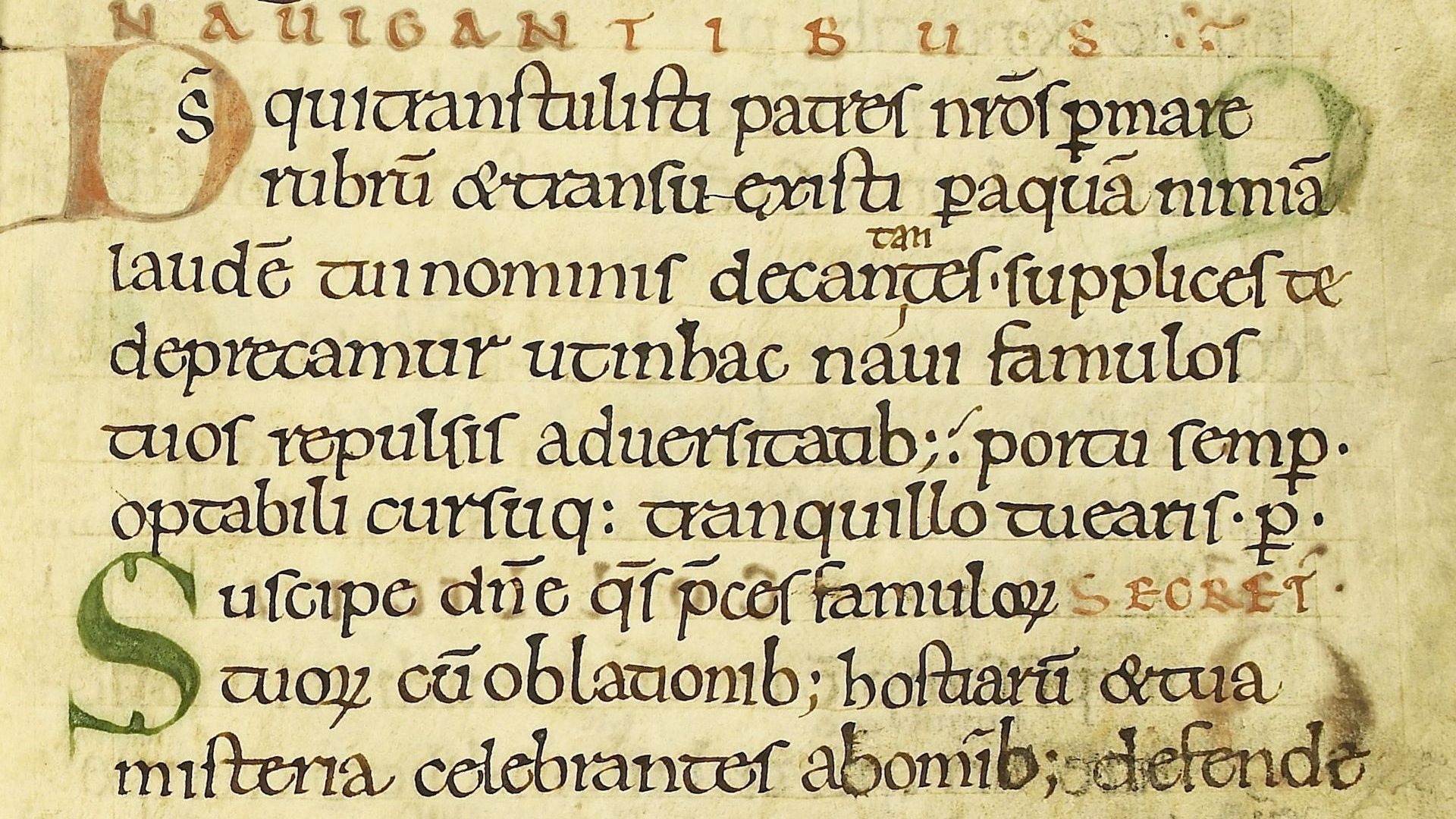

Major advances in intellectual culture took place during the Middle Ages, such as the development by monks of Carolingian minuscule in the 8th century, a efficient system of handwriting, which included standardisation of punctuation, use of upper and lower case and word spacing. Use of this script spread across Europe and made reading and writing more efficient. Today most of our knowledge of classical Latin texts is based upon manuscripts copied by Charlemagne’s scribes using this script, which later provided the basis for the development of print typefaces.

The Middle Ages was a period of developing scholarship, of advances in mathematics, science and medicine. When cities declined in importance during this period, monasteries and convents became centres of economic activity, innovation and learning, social care and medicine. Hospitals proliferated, established and maintained by monasteries and churches and faculties of medicine were established. The monasteries also laid the foundation for universities.

By the Late Middle Ages, Europe had grown prosperous. Agriculture flourished during the Medieval Warm Period from 950-1250. Populations increased, and people grew taller, a sign of good health and prosperity. (Europeans would not grow to be as tall again until the early 20th century.) This was the era in which the great cathedrals were erected, paid for by the wealth of thriving economies.

Popular misconceptions about the Middle Ages abound. One is the view that people in the Middle Ages thought the earth was flat, an idea which was promoted by some prominent 19th century authors. In fact there was never a ‘flat earth’ period among European scholars. In the 13th century, Thomas Aquinas had cited the roundness of the earth as an example of an accepted scientific truth. Stephen Gould has commented that “all major medieval scholars accepted the Earth’s roundness as an established fact of cosmology”. It is ironic that thought-leaders who wished to promote the idea of a conflict between science and religion, in order to demonise religion and exalt science, found it necessary to invent ‘facts’ to support their thesis.

It is striking how popular understandings can distort and massage history to conform to a cultural bias about history as progress. The great witch-hunts of Europe did not take place in the ‘Dark Ages’, which was a period when church authorities repeatedly rejected persecution of people for witchcraft. Rather they took place during the Renaissance, the Reformation and the Enlightenment, the supposed period of ‘light’ after darkness.

In contrast to the idea that Roman Antiquity was a period of ‘light’ and the Middle Ages ‘dark’, the institution of slavery gradually declined throughout the Middle Ages, discouraged by the church, and it had largely disappeared in western Europe by the 11th century. Before this the Vikings had been prolific slavers, selling hundreds of thousands into Islamic and Byzantine slave markets from the 6th into the 11th century and the rejection of the slave economy in Scandinavia coincided with the conversion of the Vikings to Christianity. It was only after the Middle Ages, in the Age of Discovery, that Europeans recovered an appetite for slavery.

Another popular myth is that the ‘Dark Ages’ were periods of violence and warfare. In fact wars in the medieval period cannot be compared in terms of the sheer number of casualties to the wars of Antiquity, nor to the violence of centuries after the Middle Ages, including massacres of Jews which accompanied the Black Death, the horrific Thirty Years War in the 17th century, the Napoleonic wars of the 19th century, or the two World Wars of the 20th century.

The myth claims that science was oppressed by the church, but in reality reason and ‘natural philosophy’ were held in universally high esteem during the medieval period, and scholars had no reason to fear the interference of church authorities in their work. The so-called ‘Dark Ages’ was a time of scientific innovation and advance, particularly during the High Middle Ages. John Heilbron has argued in The Sun in the Church: Cathedrals as Solar Observatories that the church invested more money and social support into the study of astronomy from the Middle Ages through to the Enlightenment, than any other institution.

It is hard to overstate the importance of the monastic system for the advance of science and culture across Europe. The monasteries, with their emphasis on training and learning, and continent-wide networks, provided a context for the steady advance of agriculture, which underpinned the growing prosperity of Europe. Many leading contributors to scientific inquiry were members of religious orders. Hildegard of Bingen (d. 1179), a Benedictine abbess and mystic, is considered the founder of scientific natural history in Germany for her botanical and medicinal writings, which arose from charitable work caring for the sick in the convent hospice. Robert Grosseteste, Bishop of Lincoln (d. 1253) and the Franciscan friar Roger Bacon (c.1292) are considered fathers of the modern scientific method. Bacon’s work in optics laid the foundation for the mathematical advances of Newton and Descartes. Copernicus (1543) was a Dominican and doctor of canon law who worked throughout his life under the patronage of his uncle, the Prince-Bishop of Warmia in Poland. The Augustinian friar Martin Luther (d. 1546) was a product of the monastic education system. His translation of the Bible and apologetic tracts established a standard for modern German, which unified the very diverse German dialect regions into a single cultural community. Luther’s broadsheets, published to promote the Protestant Reformation, were forerunners to the development of the first newspapers in the 17th century.

It is sometimes alleged that Europe was held in the grip of the Dark Ages until writings of Greek philosophy, preserved in Arabic, were translated into Latin, triggering off the Renaissance. In fact the main works of Aristotle, Plato, Euclid, Ptolemy, Archimedes and Galen had been translated into Latin by 1200, for the most part directly from Greek. While translations from Arabic, particularly of commentaries, did make a contribution, it was the fall of Constantinople in 1453, and the flight of refugee Greek scholars into the northern Italian states, bringing their manuscripts with them, that helped trigger the revival of the study of Greek as a core component of the Renaissance curriculum.

The idea of history-as-progress has so entranced the contemporary secular mind that the Reformation has been falsely recast as a progressive historical movement. In fact reformatio was already a prestigious concept from the High Middle Ages, and it meant restoration by returning ad fontes to origins. Francis of Assisi (d. 1226) was considered a reformer because he called people to emulate the example and teaching of Jesus as found in the gospels. Martin Luther’s Protestant Reformation sought to strip away accretions which the church had accumulated over the centuries, taking the Bible as the sole authority for belief and practice. When Luther urged the German nobility to embrace their freedom in the face of papal claims, he argued his case from the Bible. Likewise the Catholic counter-reformation of the 16th and 17th centuries sought to restore church institutions by returning them to their spiritual roots.

During the 1960’s and 1970’s many western intellectuals eagerly anticipated the imminent disappearance of religion. In 1966 eminent Canadian-American anthropologist, Anthony Wallis, wrote in his textbook Religion: An Anthropological View: “The evolutionary future of religion is extinction based on extensive empirical research I’m sure. Belief in supernatural beings and supernatural forces that affect nature without obeying nature’s laws will erode and become only an interesting historical memory.” The desire for religion to have no future recruits the myth of the Dark Ages to advance its apology against religion. This reduces what was a rich and complex period of European history to a crude stereotype, and damages our society’s intellectual capacity to engage with and understanding the contribution faith has made to our cultural and intellectual history.

In 1967 British sociologist Susan Budd published a study of the reasons why people reject faith. She investigated 150 leading members of the British Secular Freethought movement from 1850 to 1950 and found that in the great majority of cases loss of faith could not be attributed to their acquiring scientific knowledge. Only two reported reading Darwin or Huxley before losing their faith. The triggers for rejecting Christianity were mainly personal and moral, such as doubts about the nature of sin and punishment, concerns about the goodness of God in the face of personal experiences of human suffering, and disappointing encounters with church leaders. Charles Darwin himself lost his faith, not because his theory of evolution made God redundant, but due to personal issues, culminating in the the tragic death of his ten year old daughter Annie.

In the light of Budd’s findings, one might wonder whether the wholesale rejection of faith that began in Renaissance Humanism, flowered during the Enlightenment, and continues apace to this day, had more to do with the trauma of the Black Death in the 14th century and the Thirty Years War in the 17th century, than to the fabled ‘Dark Ages’ resistance of the Christian church to science.

PERIODS IN EUROPEAN HISTORY

Late Antiquity 4th-8th centuries

Early Middle Ages 6th-10th centuries

Medieval Warm Period 9th-13th centuries

High Middle Ages 11th – 13th century

Late Middle Ages 14th – 15th century

Little Ice Age 14th-19th centuries

Renaissance 15th-16th centuries

Age of Discovery 15th-18th centuries

Protestant Reformation 16th-17th centuries

Enlightenment 18th century

Modern Period 19th-20th centuries

________

A version of this article was published by Lapido Media in Religious Literacy: An Introduction.

Dr. Mark Durie is an academic, human rights activist, Anglican pastor, a Shillman-Ginsburg Writing Fellow at the Middle East Forum, and Adjunct Research Fellow of the Arthur Jeffery Centre for the Study of Islam at Melbourne School of Theology.

No Comments