16 Dec Divisive Victoria: Promotes Islam, Shuns Christianity

In the lead-up to the recent Victorian election, Premier Daniel Andrews announced grants of more than $8 million to the Victorian Islamic community. A social media video posted by his office celebrated this news in a way that can only be described as joyful. In the video, Andrews stated that $3 million will fund education to tackle “Islamophobia”. He also declared that Victoria will be funding Muslims to spread the word of Islam:

We think it is important, as part of an education process, that everyone across our state knows about the works of the Prophet Muhammad, Peace Be Upon Him. It’s very important that his teachings, his life, his journey, is understood by so many people. That’s why we will provide a $500,000 grant to the Islamic Museum in partnership with the Board of Imams and also the Islamic Council of Victoria to develop a program to educate, to share those teachings, that wisdom. This is part of a comprehensive plan to do what matters.

This sounds awfully like state-funded proselytism.

Of course it is important that people know about Muhammad’s deeds, teachings, and life. However, we can expect that the information made available to Victorians through this largess will be more promotional than informative. It will urge Victorians not only to respect but also to believe in the message and mission of Muhammad.

The figure of Muhammad is complex, contradictory, and controversial. At times, he advocated for what today would be recognised as justice – for example, caring for widows and orphans. At the same time, Muhammad’s works and words stand behind the many strict restrictions and punishments applied by Islamic legal codes. The Afghan Taliban has forbidden car drivers, restaurants, and public media from playing music, based on Muhammad. Qatar banned alcohol from the FIFA World Cup and bans homosexual acts, based on Muhammad. Saudi Arabia applies the penalties of amputation and cross-amputation (cutting off opposing hands and feet), based on Muhammad. Indonesia has recently banned sex outside marriage, reflecting religious beliefs based on Muhammad. Similar bans are in place in other Muslim-majority nations, including Pakistan, Qatar, Iran, Somalia, and Sudan.

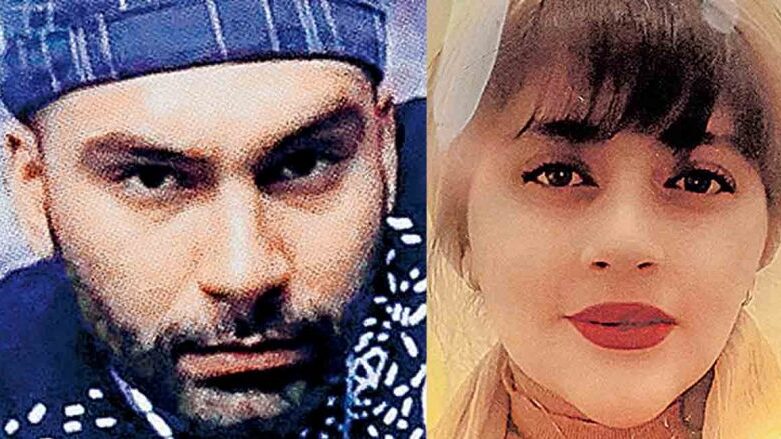

An example of Muhammad’s influence is found in legal statutes of Iran. As the wave of protests continue across Iran three months after the death in custody of Mahsa Amini, the Iranian state has begun executing protesters. The first to be put to death was Mohsen Shekari, who was convicted of blocking a street and wounding a member of the basij, a religious militia that forms part of the Iranian Revolutionary Guard.

Mr Shekari was convicted under the Islamic Penal Code of Iran. His crime was to ‘wage war against God’ and cause ‘corruption on the earth’. This crime, known as moharebeh in Persian, and its punishment are defined in articles 279-288 of the Islamic Penal Code of Iran. This law is based on a verse of the Quran that states:

The punishment of those who wage war against God and His Messenger, and strive to spread corruption in the land, is to be killed, be crucified, have their hands and feet on opposite sides cut off, or be banished from the land. This will be to shame them in this world, and a great punishment will be theirs in the next life. (Sura 5:33)

The Islamic Penal Code of Iran states that the crime of moharebeh is committed when someone takes up a weapon to cause terror or to ‘breach public security and freedom’. This is one of half-a-dozen illegal acts, known as hudud crimes, for which a specific Islamic penalty is understood to have been mandated by God.

Following Sura 5:33, the Islamic Penal Code of Iran specifies that for moharebeh, one of four punishments is to be applied, at the discretion of a sharia judge: the death penalty; crucifixion; cross-amputation (cutting off the right hand and left foot), or banishment.

According to Islamic tradition, the verse referring to waging ‘war against God’ was revealed to Muhammad after some men who had killed a shepherd were killed by Muhammad’s orders. Their eyes were put out, their arms and legs were amputated, and they were left to die in the desert. Sura 5:33 clarifies the punishment for such cases, which is actually more moderate than the retribution imposed by Muhammad.

Andrews’ enthusiastic praise for Muhammad, and his glowing praise of the Muslim community – including a declaration that he will always ‘stand’ with them – contrast starkly with his recent vilification of conservative Melbourne Anglicans for their views on abortion and same-sex marriage. He called their views ‘intolerance’, ‘hatred’, ‘bigotry’, and ‘absolutely appalling’. Ironically, Andrews was castigating Victorian Christians for holding views that very many Victorian Muslims also hold.

Our culture manifests two opposite, extreme approaches to religion, both flawed. One is to treat religion as something that is merely a part of culture, perhaps at times rather odd, but essentially of secondary importance. In a sense, this is what Andrews has done with Muhammad, for his glowing praise is vacuous and treats with dismissive contempt the actual content of Muhammad’s words and deeds. It is as if the profound impact of Muhammad on millions of men’s, women’s, and children’s lives is irrelevant and deserves no critical reflection.

The other extreme response to religion is to vilify and demonise. Andrews’ response to the beliefs of some Victorian Anglicans about abortion and marriage was an example.

Religion is too important to be abused in these ways. The American journalist Andrew Breitbart observed that ‘politics is downstream from culture’. And culture is downstream from religion. Over time, religions have tremendous power to shape cultures and, through them, politics and law, both for good and for evil.

In our religiously diverse society, the worst thing to do with religious differences is to manipulate extreme simplifications and stereotypes for crude political gain. We need political leaders who can forge a better religious policy path than this.

This is an edited version of an article which first appeared in the Spectator.

Mark Durie is the Director of the Institute for Spiritual Awareness, a Senior Research Fellow at Melbourne School of Theology and a Writing Fellow for the Middle East Forum.

Jenny O'Brien

Posted at 21:44h, 17 DecemberWhy am I not surprised at what Daniel Andrews is up to now. Typical.

stuart lawrence

Posted at 19:52h, 20 Februarythe qld police think christians who murder police officers are terriosts and yes christians can terriose innocent people through bombs shootings etc

Margaret Reyne

Posted at 12:41h, 23 OctoberAmen

Thank you for sharing wisdom.