05 Sep Complexity, Truth and the Islamic State: a Response to John Azumah and Colin Chapman

Recently Lapido Media published an article of mine entitled ‘Three Choices’ and the bitter harvest of denial: How dissimulation about Islam is fuelling genocide in the Middle East. In it I argued that Western theological illiteracy, made worse by demonstrably false statements put out by scholars, has weakened leaders’ and governments’ capacity to manage the risks associated with Islamist radicalism.Because of this illiteracy Western leaders have had great difficulty grasping the implications of the global Islamic revival, especially its impact upon religious minorities.

I referred to three Christian scholars whose writings are examples of this problem: Miroslav Volf, Colin Chapman and John Esposito.

Colin Chapman and John Azumah have responded to my article (see here, here, and also here), to which I am responding in my turn with this article. Some of the points raised by Chapman and Azumah require detailed documentation, so to assist readers I have relegated a good deal of my supporting evidence to endnotes.

I shall first make some general points about the relationship between faith and human action. (These points are elaborated in The Third Choice: Islam, Dhimmitude and Freedom.)

Human behavior has many causes, religion being one of them

When writing about Islamic violence it is essential to emphasise, first of all, in Aleksandr Solzehnitsyn’s words, that “the line separating good and evil passes not through states, nor between classes, nor between political parties either – but right through every human heart – and through all human hearts.”1 To which we must add: “nor between religions”. Christians have been and continue to be guilty of human rights abuses and inhumanity to others, as have Muslims. It is not rational or evidence-based to single out one religious community as the source of all evil in the world. No religion has a monopoly on hypocrisy and evil.

It is necessary to emphasize, that while religions – and ideologies in general – can influence human behavior, they are not the only influence. Many other factors come into play as well, such as culture, societal structures, individual, group and national and all sorts of human desires. Consider, for example, the WWII Holocaust. Nazi racist ideology was a powerful driver of the Holocaust, but it was not the only driver. There was also, for example, plain old greed: the greed of the many individuals who profited from the destruction of European Jewry through looting their properties and possessions.

The influence religions wield is often mediated. Most people do not walk around with Bibles or Qurans in their pockets, checking holy scripture for every tiny act they perform. Instead they rely on habits, culture, personal life history and how they have been taught and formed throughout their lifetime. Religious influence is mediated over time through complex processes which include worship and other forms of religious observance, education, family life, and culture.

When religion does influence behavior, the effect is often not absolute. Religiously inclined people are social and cultural beings, who can and do make very individual choices, so their acts, even which influenced by religion, are often not absolutely determined by it.2

It remains true that religions can and do influence behavior, and the extent of this influence can be profound, the multiplicity of other influences notwithstanding.3

Religions which are based upon a canon – foundational texts – periodically go through renewals of belief and practice during which believers attempt to strip away accretions in order to bring their faith closer to what they find in these texts. This is a bit like travelers on board a ship who remember from time to time to consult their compass, after which they reset their course. When this reset happens, the influence of a religion’s canon can increase,

while other influences on human behavior get comparatively weaker.

In our present era Islam is going through a long drawn-out global reset. Women putting on veils in their millions are but one of many changes in behavior inspired by the renewed influence of the Quran and the Sunna. At such a time it is rational and reasonable to measure the actions of believers against the texts to which they look for inspiration.

In summary, while it is simply not possible to reduce each and every example of human action to religious principles, or verses found in ancient texts, it is nevertheless true that religions do influence behavior in important ways which deserve to be acknowledged, especially when a religious reformation is underway.

The complexity of the interaction of faith and action notwithstanding, we should not be surprised when revivalist Muslims seek to implement principles found in the Qur’an or Islamic legal textbooks.

Colin Chapman

The most important point about Colin Chapman’s response is that he did not respond. He had nothing to say to my claim that he misrepresented the function of the jizya tax paid by Christians under Islam. There remains a world of difference between paying a tax to avoid military service and handing over gold to keep one’s head.

The two objections Chapman does make are that he ‘suspects’ I have oversimplified history, and that I ‘seem to believe’ that everything can be explained by appealing to texts.

Regarding ‘oversimplifying’, Chapman offers a handful of snippets of historical information which are tangential to the arguments I presented. Moreover his claim that ‘conversion of large numbers of Christians came after two or three centuries’ is contradicted by readily available evidence reported in standard histories.4

Concerning Chapman’s second objection, I do not and have never believed that everything can be explained by appealing to texts. Nevertheless that is not to say that texts are unimportant. An illustration of their importance was the announcement of the Islamic State that it was offering the Syrian Yazidis but two choices (see here and here) – conversion or death – with no option of paying jizya. This was in accordance with Sura 9:29 of the Quran, which offers the alternative of paying jizya only to the ‘People of the Book’, a category which IS claims the Yazidis do not fit.

In Iraq and Syria today people are being killed in patterns shaped by what is written in Islamic texts. This being the case, it is rational and reasonable to engage with those texts and to point how they are influencing actors on the ground.

John Azumah

In his critique, John Azumah attributes views to me which I do not hold.

I do not believe that ‘everything can be proven or disproven by drawing a straight line between text and action’.

I do not deny that there are ‘intervening and mediating socio-political, ethnic, cultural, economic, historical and existential factors’ which all contribute to determining the behavior of religious people.

I do not ‘refuse to take such extra-textual forces into account’.

None of this means that it is illegitimate to explore the textual authorities which the Islamic State claims guide its activities.

John Azumah presumes that I have condemned Islam based upon Boko Haram’s actions (here), and that I do this in a prejudiced, ignorant way. But he puts the cart before the horse. In reality what I have sought to do it so evaluate Boko Haram’s actions against the teachings of the faith it professes. My purpose was not to condemn Islam, but to understand and explain Boko Haram.

It is disappointing that Azumah makes sweeping generalizations about my views without engaging with any specifics. For example he claims that my ‘attitude’ to Qasim Rashid’s arguments about Boko Haram was ‘dismissive’, but he did not find fault with the reasoning which lead me to this conclusion. In reality I treated Rashid’s arguments with respect by engaging with them in serious way. This is the opposite of being dismissive.

Similarly, Azumah’s claim that I was ‘selective’ in the sources I cited does not hold water. For example, when I pointed out that IS’s announcement that conquered Christians have three choices, and explained how the very phrases IS used are found in Islamic sacred texts, no amount of alternative citations could have detracted from this point.5

In response to Azumah’s suggestion that I was ‘disingenuous’ – which is to say, dishonest – when I stated that IS is perfectly capable of defending its ideology, I re-assert that they are able to defend their views. Whether

one thinks their Islam is valid is another matter: my point is that they have a well thought-through position which aspires to be authentically Islamic and has evidence to back it.

Azumah seemed particularly trouble by my suggestion that IS claims to justify its murderous campaign as a ‘jihad’. Not so, he says, because ‘they have no legal leg to stand on … this is the preserve of a legitimate ruler, not a band of terrorists’.

To be precise, the mainstream view in sharia law is that only the caliph – what Azumah refers to as ‘a legitimate ruler’ – can wage aggressive jihad against infidels outside of the house of Islam. But this begs the question: Whose rule is legitimate? This is a key issue in understanding Islamic radicalism. There have been many instances in recent decades of leading Islamic jurists issuing fatwas in support of jihadis whom others might label as terrorists. For example many eminent scholars across the Sunni Muslim world declared jihad in June 2013 against the Assad regime. According to these scholars the fighters of IS were pursuing a legitimate jihad in Syria.6

In the light of such declarations, does Azumah really mean to claim some kind of higher Islamic authority to rule that all these scholars were out of line? Does he really imagine that when they issued their fatwas, these scholars had never heard of the principle that only a caliph can declare an aggressive jihad against infidels, and that they did not take this into account when they declared Assad’s rule to be illegitimate?<#note-51076d70″>7

Azumah points out that Kurdish fighters are Muslims too, as a riposte to my claim that IS is seeking to act in accordance with Islamic sources. Azumah writes: ‘if it is justified to judge Islam on the basis of the actions of jihadi groups, how then can we explain the actions of Kurdish Muslims who are fighting and dying to protect Christian and Yazidi minorities? The Kurds are also Muslims, reading the same Quran, following the same prophet and performing the same daily prayers.’ As with Boko Haram, my point was not to judge Islam, but to understand the IS jihadis, and this comparison with the Kurds actually supports my thesis. Human behavior has complex motivations, and not all Muslims’ actions can be explained in terms of their religion. The Kurds may be Sunni Muslims, but the point is that they are fighting for national independence, not the dominance of their religion. As one Kurdish soldier put it, ‘They always shout “Allahu akbar”. We shouted “Long live Kurdistan”.’

Both Azumah and Chapman take exception to my statement that ‘In reality Islamic coexistence with conquered Christian populations was always regulated by the conditions of the dhimma, as defined above, under which non-Muslims have no inherent right to life, but had to purchase this right year after year.’ They stress that conditions for Christians living under Islam varied in time and space, and with this I can only agree: the jizya and other dhimma regulations have not always been imposed consistently, least of all in the modern period: there have been many local variations and elaborations, and at times also omissions of application.

Nevertheless I stand by my statement that it is the theological construct of the dhimma, together with its conditions, which has consistently furnished the ideological framework for regulating the treatment of conquered Christian communities.8

Why such resistance to theological explanations?

At the heart of Azumah’s objection to my article is not the fact that there are correlations between IS abuses and Islamic sources, nor even that some Western scholars have made false claims about jihad and the dhimma.

The nub of the matter for Azumah is his aversion to calling Islam the problem. He is perfectly aware of the texts which are cited by Islamic radicals and does not deny their influence. However as a strategy for engagement he believes we must not problematize Islam itself “because it can go nowhere.”

Azumah believes that to call Islam the problem could have negative consequences:

• it would alienate Muslims who oppose radicalism;

• it would justify radical ‘twisted zealots’ – by validating their ‘excuses’; and

• it would inspire more fear, hatred and violence (Azumah even refers to bombing the Ka’bah in Mecca).

Azumah believes that problematizing Islam will fatally damage the vitally important process of reconciliation, because blaming Islam for the barbarity of some Muslims can only fuel anger and hatred towards Muslims on the one hand and incite more hate from Muslims on the other. He fears that naming Islam as the problem could trigger unresolvable catastrophic – even apocalyptic – global conflict.

I take exception to Azumah’s argument on two grounds.

First, the argument from adverse consequences is a logical fallacy. It is an argument based on fear, not on truth. Azumah’s position pre-judges the question of whether and to what extent Islam itself is responsible for the problems Muslims face.

Second, I do not accept that Azumah’s feared consequences necessarily follow, and to the extent that they might, they do not necessarily outweigh the negative consequences of not making truth the standard of our explanations, rather than fear. This is in itself a subject which deserves more extensive comment than is possible here. Some key points are:

• arguments against radicalism by moderate Muslims which do not hold up to scrutiny offer only flimsy, unstable protection against radical violence: because they are unsustainable in the end they only make problems worse by concealing their true nature;

• it is immoral to equate explaining the reasoning of evildoers with justifying their acts;

• to name Islam as the problem is not the same thing as inciting hatred against Muslims, not least of all because Muslims suffer so much disadvantage from problems of Islam.

• to conceal the causes of injustice is to partner with it.

If Azumah’s critique of my article has been shaped by the fear of negative consequences, Chapman’s response shows a concern with other influences apart from religion, including Western imperialism, Zionism, or global politics. One might add other factors to Chapman’s list, including chronic economic failure and disillusionment across the Middle East, a demographic explosion of youth and young adults, and the legacy of decades of dictatorship and military rule. However Chapman has a record of ignoring or overlooking historical evidence and suppressing complexity when weighing the contribution of Islamic theology against that of Zionism in the Palestinian-Israeli conflict.9

The fact that there can be multiple issues at play is not in itself an argument against the influence of religious motivations. Human behavior has varied and complex causes but this does not disprove the significance of religion as an explanation for human actions.

Conclusion

The question of whether Islam is the cause or the pretext for the Islamic State’s violence is clearly a sensitive one. While acknowledging that there are complex factors which have contributed to the emergence of IS, it nevertheless remains the case that this fledgling would-be state’s policies show remarkable influences from early Islamic texts. Moreover the emergence of a living, breathing implementation of ancient policies cannot be considered surprising, in the light of the teachings of the global Islamic revival, which has been building up steam for more than a century.

In response to John Azumah: it is unhelpful to declare Islam itself beyond critique for fear of negative consequences. That is intimidation.

In response to Colin Chapman: history matters, and to deal with the facts of history objectively, including understanding the contribution of sacred texts, means not letting one’s personal preoccupations – such as antipathy to Zionism or Western colonialism – cloud and distort one’s understanding of the present.

There can be many reasons for denial. Understanding those reasons is important, whether the reason is fear or some kind of bias. But the fact remains that the Islamic State does pride itself on being Islamic; it is a manifestation of the global Islamic resurgence; and the inspiration it finds in the canon of Islam (the Quran and Sunna) can help us to understand. We should have been able to anticipate many of its worst excesses.

Mark Durie is the founding director of the Institute for Spiritual Awareness, a Fellow at the Middle East Forum, and a Senior Research Fellow of the Arthur Jeffery Centre for the Study of Islam at Melbourne School of Theology.

NOTES

1. Aleksandr Isaevich Solzhenitsyn, The Gulag Archipelago, 1918-1956: An Experiment in Literary Investigation. New York, Harper and Row, p.25.

2. Consider for example the influence of Islamic teachings on the practice of female genital mutilation. While there are grounds in Islam which can be adduced in support of this practice (see here for a summary of a mainstream explanation), the way in which this is practiced varies according to local conditions. For example it is only in some parts of Africa that infibulation is practiced, which is a form of female circumcision which nothing in Islam can explain. As another example, consider that sharia law law bans music, but music is much loved and performed in many Muslim communities, Islamic law notwithstanding.

3. For example no-one could deny that the reason polygamy is legally practiced in many Muslim societies today is linked to Islam’s teachings. Nevertheless not all Islamic nations have legal polygamy: both Tunisia and Turkey have banned the practice, under the influence of modern ideas, so even here the influence of the religion is not absolute. Another example is the specific distribution of female circumcision across Muslim societies. Although variation in the extent of Islamic female circumcision cannot be predicted from Islamic teachings, its distribution can. Since it is only in the Shafi’i Islamic school of law that the practice of female circumcision is mandatory, it should be no surprise to find that Muslims practice female circumcision most where Shafi’i law predominates. For example female circumcision is practiced in Saudi Arabia in Shafa’i areas, but not where the Hanbali code is followed. It is found in Southeast Asia (Malaysia, Bahrain and Indonesia) where the Shafa’i code is followed, but not in India where the Hanafi code predominates. It is found in Egypt, which is mainly Shafi’i, but not in neighbouring Libya which is Maliki. It is found among the Kurds of Iraq, who follow the Shafi’i school, but not among Iraqi Sunni Arabs, who follow Hanafi jurisprudence.

4. The Cambridge History of Islam edited by P.M. Holt, Ann K.S. Lambton, and Bernard Lewis reports that already during the Ummayyad Caliphate (661-750), in the first 120 years after Muhammad: “large numbers of non-Muslims embraced the faith of their conquerors. … One reason was certainly eagerness to come nearer to the new masters, and to share the advantages the latter enjoyed, not least among which was that of being far less heavily taxed.” In The First Dynasty of Islam: the Umayyad Caliphate AD 661-750, (Routledge 2006, p.8) G. R. Hawting writes that by the end of the Umayyad period “large numbers of the subject peoples had come to identify themselves as Muslims,” and “the Muslim sources have many references to the difficulties caused to Umayyad governors of Iraq and Khurasan when large numbers of non-Arab non-Muslims attempted to accept Islam … in the early decades of the eighth century”.

The classical study of this subject, D. C. Dennett’s Conversion and the Poll Tax in Early Islam, argued that while a simple line cannot be drawn between jizya and conversion – for a whole host of reasons – there were indeed large numbers of converts in the first few centuries, in variable patterns depending upon local conditions, and the tax regime was one factor which influenced conversion.

Bulliet’s study of conversion in the early Islamic centuries (Conversion to Islam in the Medieval Period: An Essay in Quantitative History, Harvard University Press, 1979) argues that in most of the conquered areas the process of mass conversion conversion was well under way by the end of the second century, and even in the first century a significant proportion of the conquered populations had converted to Islam, the pattern varying from region to region. Concerning Egypt, Mu’awia, the first Ummayad Caliph (d. 680) is reported to have said that already in his time the population of Egypt was one third Arabs, one third converts, and one third Copts (i.e. Christians) (A. S. Tritton, The caliphs and their non-Muslim subjects, p.1) John of Nikiu, eyewitness to the conquest of Egypt, reported that many Christians converted even at the time of conquest. The Coptic History of the Patriarchs states that around 700 AD, many people were forced to become Muslims. It reports also that in 727 AD 24,000 Copts converted to Islam in order to escape the jizya, and in 750 AD ‘because of the heavy taxes and the burdens imposed upon them, many rich and poor denied the religion of Christ.’ Al-Maqrizi reported that Muslims had become a majority in Egypt by the 9th century. (See Shaun O’Sullivan, 2006 ‘Coptic conversion and the Islamization of Europe’, Mamlūk Studies Review 10.2: 65-69).

In my article for Lapido I presented four citations which made the point clear, but there were many more that could have been used instead. One view I was critiquing, that the jizya was an exemption from military service, did not even appear in the historical record until the late 19th century. This first only appeared after the Ottomans had replaced the jizya with a military exemption tax, the baddal-askari, in 1856.

6. Not all Muslim scholars agreed: a contrary view was put forward by Damascus-based Sunni scholar Sheikh Al-Buti, before he was killed by a Sunni suicide bomber.

7. By denigrating jihadis as being akin to the 7th century Kharijites, Azumah follows the line of Saudi authorities, who have used this label in an attempt to stigmatize jihadism. However Madawi Al-Rasheed in his study of Saudi jihadi movements, locates jihadi violence, not at the margins of interpretation, but at its centre:

“The terrorist attacks of the 1990’s, which increased in frequency and magnitude in 2003–4, are not senseless and aimless acts by a group of alienated youth, often described in official religious and political circles as khawarij al-‘asr (contemporary Kharijites). Perpetrators of violence are guided by cultural codes that draw on sacred texts and interpretations by religious scholars who claim to return to an authentic Islamic tradition, found not only in al-kitab wa ’l-sunna (the book and the deeds of the Prophet) but also in medieval and more recent commentaries on the texts by famous religious authorities among aimat al-da‘wa al-najdiyya (Najdi religious scholars). Jihadi violence is not at the margin of religious interpretation, but is in fact at its centre; hence the difficulties in defeating the rhetoric of jihad in the long term.” (Madawi Al-Rasheed, ‘Rituals of Life and Death: the politics and poetics of jihad in Saudi Arabia’, in Dying for Faith: religiously motivated violence in the contemporary world. Ed. Madawi Al-Rasheed and Marat Shterin. I.B. Taurus, 2009, p. 81.)

8. This is true even when the implementation has been partial and limited. Even in a nation such Indonesia – where the Christian populations were never conquered in the first place – the present-day treatment of churches is shaped by dhimma principles. For example the great difficulty of gaining official permits for new church buildings in Indonesia and the associated practice of using this as a pretext to demolish churches (see here) aligns with the dhimma principle that no new non-Muslim places of worship can be built under Islamic rule. In Egypt, where regulations limiting building and renovation of churches are even more discriminatory, the underlying theological driver is the same.

Another example of the far-reaching impact of the dhimma worldview was the crippling Varlık Vergisi tax imposed in a discriminatory fashion upon Turkish Christians during WWII. This contributed greatly to the destruction of Christian communities in Turkey, compelling many to emigrate. Like the Ottoman’s abolition of jizya almost century before, this tax was only removed at the insistence of Western powers. While technically it fell outside of dhimma regulations, like the jizya it was a manifestation of a worldview that considered Christians as owing a debt to the Muslim community and found it acceptable to apply a policy of ‘plunder by taxation’.

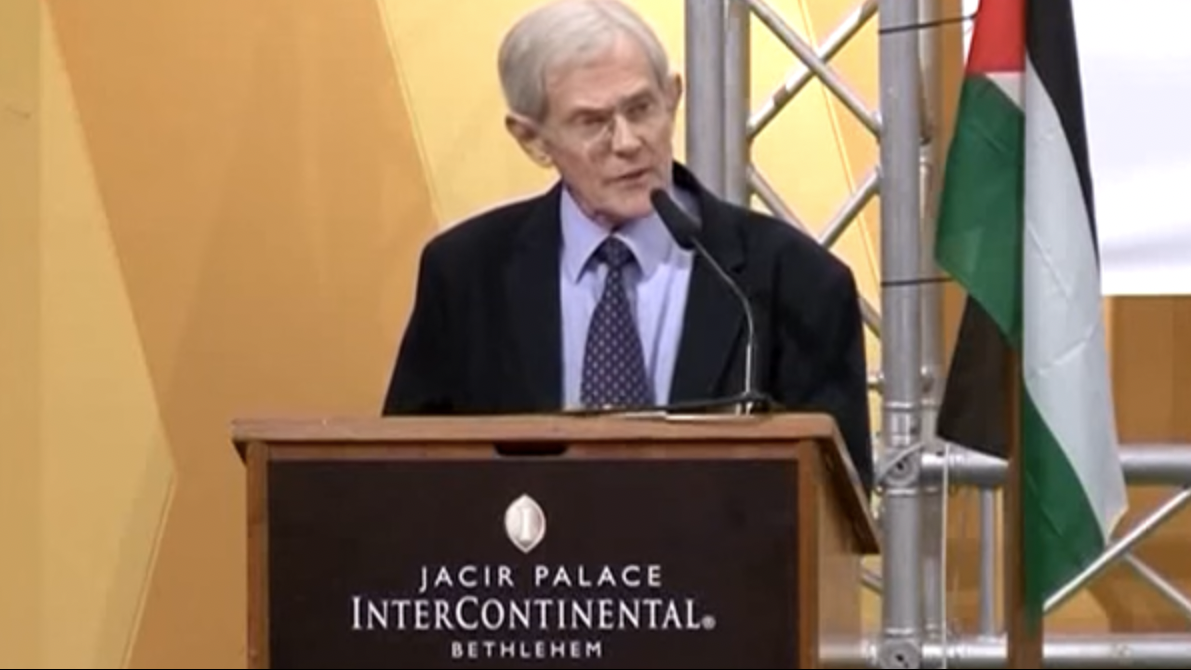

9. For example, he has written that ‘the first occasion when any Arab government invoked the doctrine of jihad [against Israel] was in 1969’ (“Evangelicals, Islam and the Israeli-Palestinian Conflict”, an unpublished paper presented at the Christ at the Check-Point conference, March 2010. Chapman’s videoed presentation can be viewed here: see from 28:40), but in fact King Abdullah of Jordan announced in May 1948, referring to the war with Israel: “He who will be killed will be a martyr; he who lives will be glad of fighting for Palestine … I remind you of the Jihad and of the martyrdom of your great-grandfathers,” and in December 1947 Al-Azhar scholars called for a ‘worldwide jihad in defense of Arab Palestine’, in an effort to annihilate the Zionists (Benny Morris, 1948: A History of the First Arab-Israeli War, Yale University Press, 2008, p. 65, 209). The Al-Azhar fatwa was widely reported in international media at the time. There was also a further 1956 Al-Azhar fatwa prohibiting reconciliation with Israel “peace with Israel, so-called by those who have an interest in it, is forbidden by the Islamic religious ruling, because it allows the plunder to keep his loot and recognizes this plunderer’s right to it… the Muslims are forbidden to reconcile with the Jews who had robbed the land of Palestine and assaulted its people and their possessions, in any way that allows the Jews to remain as a state on this holy Islamic land. All Muslims, moreover, must cooperate in order to take this land back from the hands of the plunderers and they should place weapons in the hands of the Mujahideen’ so that they can launch a ‘Jihad’ for that purpose.” (Ephraim Karsh and P.R. Jumaraswamy, Islamic Attitudes to Israel, Routledge, 2013, p. 58).

No Comments